Incoming Events

In Stone.js, the IncomingEvent is the heart of your application. It represents the intention that your system must respond to. This intention doesn’t come out of nowhere, it’s born from a cause in the external world.

That cause, an HTTP request, a CLI command, a cloud event, is captured and interpreted by an adapter. The adapter translates it into an IncomingEvent, and it’s passed through the system for processing.

In the Continuum Architecture, every application begins with an intention. That intention is always modeled as an IncomingEvent.

Even though it’s created by the adapter in the integration dimension, the IncomingEvent belongs to the initialization dimension, where the core logic and internal context live. It is part of the internal flow of your application, not a raw input you manipulate freely.

You cannot mutate or instantiate an IncomingEvent directly. It is created internally by the adapter, and as a developer, you only participate in its creation via adapter middleware. Once received, it is treated as immutable. You can read from it, enrich it with metadata, and respond to it, but you never replace or reassign it.

There are many flavors of IncomingEvent depending on the platform:

| Platform | Class | Example Adapter |

|---|---|---|

| Node HTTP | IncomingHttpEvent | @stone-js/node-http-adapter |

| Browser | IncomingBrowserEvent | @stone-js/browser-adapter |

| Node CLI | IncomingEvent | @stone-js/node-cli-adapter |

| AWS Lambda | IncomingEvent | @stone-js/aws-lambda-adapter |

| AWS Lambda HTTP | IncomingHttpEvent | @stone-js/aws-lambda-http-adapter |

At the base of the hierarchy is IncomingEvent, it’s not abstract. It’s the simplest usable form of an event in Stone.js, with generic capabilities like accessing metadata and locale. More specific subclasses like IncomingHttpEvent or IncomingBrowserEvent extend its behavior for their respective platforms.

Every event handler in Stone.js, whether it's your main application entry point or a specific route, receives one IncomingEvent. Your job as a developer is to respond to this incoming event, using the full expressive power of your domain.

Tips

Throughout the Stone.js documentation and for simplicity, we refer to IncomingEvent for all incoming events.

Using IncomingEvent

The IncomingEvent class is the most minimal and generic expression of an incoming event in Stone.js. It is not abstract. It is fully usable and forms the foundation upon which more specific incoming events are built (like IncomingBrowserEvent or IncomingHttpEvent). All IncomingEvent instances extend the base Event class, which provides standard metadata and utility features.

The IncomingEvent encapsulates the intention of the system, a normalized, structured version of the external cause. It holds just enough data to represent this intent internally, in a consistent and platform-agnostic way.

import { IncomingEvent } from '@stone-js/core'

const handle = (event: IncomingEvent) => {

// Access the event's properties

const locale = event.locale

const metadata = event.metadata

const timeStamp = event.timeStamp

// Use the event's source

console.log(event.source.platform) // e.g., 'http_node'

}

Key Properties

Here are the core properties of an IncomingEvent:

| Property | Description |

|---|---|

type | The immutable type of the incoming event stonejs@incoming_event. |

locale | The preferred locale for the event (default is 'en'). |

metadata | Internal metadata, modifiable via get() and set() methods. |

source | A structured object representing the original external context. |

timeStamp | The time when the event was created (milliseconds since epoch). |

The source: A Portal to the External Context

While Stone.js encourages you to operate within the internal, normalized incoming event interface, there are situations where you need to peek back at the raw, unprocessed external input, for example, to access a third-party field or inspect the raw platform context.

This is where the source property comes into play.

The source is your structured gateway to the external world. It holds everything the adapter used to build the IncomingEvent.

interface IncomingEventSource {

rawEvent: unknown

rawContext: unknown

rawResponse?: unknown

platform: string | symbol

}

You’ll typically use it for:

- Debugging and introspection

- Logging raw platform-level input

- Implementing lower-level integrations or fallbacks

Example: Accessing raw AWS Lambda input

event.source.platform // 'aws_lambda'

event.source.rawEvent // The raw Lambda event (as-is)

event.source.rawContext // The raw Lambda context object

This structure is consistent across platforms, making it easier to write adapter-agnostic fallback logic when necessary.

Important

That said, avoid relying too heavily on the source. If you find yourself accessing rawEvent often, it may be time to create a new adapter middleware to populate the necessary data into the metadata store.

Smart API (get() / set())

All IncomingEvents provide a unified API for retrieving and storing data using get() and set(). This API is designed to be intuitive, flexible, and most importantly, platform-agnostic.

event.get('user.name')

event.set('user.role', 'admin')

- Dot notation is supported for accessing or adding nested values (

user.name,user.role, etc.) - You can provide a fallback value if the key is not found:

event.get('permissions.admin', false)

- You can also add internal data using

set():

event.set('my.custom.flag', true)

All data written via set() is stored inside the metadata store, it’s safe, isolated from the raw request, and purely internal. This makes it perfect for middleware enrichment, auth flags, and request-specific context propagation.

Platform-Aware Magic

Here’s where it gets clever.

On minimal platforms like AWS Lambda or generic CLI contexts, there’s no native “body” field like you'd find in HTTP. But that doesn’t stop you. Adapters that produce an IncomingEvent from those platforms extract any structured input from the raw external context and inject it into the metadata.

That means you can use event.get('payload.message') in both environments:

- In local development with the HTTP adapter and Postman (where the payload is in the body)

- In Lambda (where the payload might be buried inside the raw

eventobject)

// Works in both environments!

const name = event.get('user.name', 'Guest')

Because IncomingEvent.get() first looks in the body (if the subclass has one), then falls back to metadata, your handler logic remains unchanged, regardless of the platform.

This gives you true cross-platform compatibility with zero branching logic. Write it once. Deploy it anywhere.

In subclasses like IncomingBrowserEvent or IncomingHttpEvent, the get() method is even smarter, it follows a prioritized lookup strategy specific to each platform (e.g., body → query → headers → cookies → metadata).

These subclass-specific strategies will be covered in detail in their respective sections.

Lifecycle and Immutability

You never create an IncomingEvent yourself. It is instantiated by the adapter when the external cause is received. This happens at the boundary between the integration and initialization dimensions.

@StoneApp()

export class App {

handle(event: IncomingEvent) {

// Read intent data, respond accordingly

}

}

Once passed to your handler, you should treat it as read-only, except for setting metadata via set(). If you need to duplicate or fork the event, use clone().

const copy = event.clone()

copy.set('custom', true)

Using IncomingBrowserEvent

The IncomingBrowserEvent is a platform-specific subclass of IncomingEvent, designed for applications running in a browser context. It is automatically created by adapters like @stone-js/browser-adapter and provides extended APIs tailored for frontend navigation, SPA routing, cookies, and client environment detection.

It includes all capabilities of IncomingEvent (e.g., get(), set(), clone(), metadata, source access), but adds features specific to browser-based use cases.

Constructor Reference

| Property | Type | Description |

|---|---|---|

url | URL | Required. The browser's full URL |

protocol | string | Optional. The connection protocol (default: 'http') |

queryString | string | Optional. Raw query string (parsed internally into query) |

cookies | CookieCollection | Optional. Pre-parsed cookies |

source | IncomingEventSource | Required. Raw external context (e.g., window/document events) |

locale | string | Optional. Locale string (default: 'en') |

metadata | Record<string, unknown> | Optional. Initial metadata for internal state |

How IncomingBrowserEvent is Created

Not all browser events are welcome here.

The IncomingBrowserEvent is created by the Stone.js browser adapter, but not from just any DOM event. Stone.js doesn’t care about click, keydown, or hover events, those belong to the UI world.

Instead, Stone.js focuses solely on navigation events, the kind that express an intention to change the page.

By default, the browser adapter listens to two events:

| Event Name | Triggered When |

|---|---|

'popstate' | User navigates using browser history (e.g., back/forward) |

'@stonejs/router.navigate' | Programmatic navigation via the Stone.js Router |

For example:

router.navigate('/posts/new') // triggers '@stonejs/router.navigate'

These events are treated as causes. When the adapter receives one, it launches the internal context pipeline, which in turn creates a new IncomingBrowserEvent, representing your new navigation intention.

Stone.js ensures this stays focused and efficient: it doesn't hijack unrelated events or bloat your event model.

Custom Events?

If you really want to extend this, you can register additional browser events to be treated as navigation causes using the blueprint:

blueprint.add('stone.adapter.events', ['my-custom-event'])

Stone.js will start listening to 'my-custom-event', and whenever it is dispatched, it will be converted into an IncomingBrowserEvent.

But honestly?

You probably won’t need this. The built-in events already cover the most important navigation scenarios.

Populating the IncomingBrowserEvent

Instances are usually created by the browser adapter automatically, you won’t need to construct them manually unless writing a custom adapter or test fixture.

But you can participate in the creation process by providing a custom protocol or locale value, using adapter middleware.

The declarative API is used for demonstration purposes, but you can also use the imperative API.

import {

BROWSER_PLATFORM,

BrowserAdapterContext,

BrowserAdapterResponseBuilder

} from '@stone-js/browser-adapter'

import { Promiseable, NextMiddleware } from '@stone-js/core'

@AdapterMiddleware({ platform: BROWSER_PLATFORM })

export class MyAdapterMiddleware {

async handle(

context: BrowserAdapterContext,

next: NextMiddleware<BrowserAdapterContext, BrowserAdapterResponseBuilder>

): Promiseable<BrowserAdapterResponseBuilder> {

context.incomingEventBuilder

.add('locale', 'en-US')

.add('protocol', 'https')

return next(context)

}

}

As highlighted, the IncomingBrowserEvent is not instantiated directly. Instead, you configure it using the incomingEventBuilder, which allows you to define the properties listed above before the incoming event is passed to the event handler.

URL and Query Access

Browser events are centered around the current document's URL. IncomingBrowserEvent provides direct access to the key parts of the URL via:

event.uri→ full URL stringevent.path→pathname + searchevent.pathname→ URL path without queryevent.query→URLSearchParamsinstanceevent.queryString→ raw query stringevent.host,event.hostname,event.hash,event.scheme

And useful helpers like:

event.decodedPathname // decoded version of pathname

event.segments // pathname split into an array of segments

event.uriForPath('/foo') // full URI with domain for relative path

These utilities are useful for dynamic rendering, navigation guards, and routing logic in SPAs.

Cookies and Query Parameters

The browser event provides full cookie support using the CookieCollection utility:

event.getCookie('auth_token', {}) // Return a Cookie object or default value

event.cookies.getValue('auth_token') // Get the cookie value directly

event.hasCookie('isLoggedIn')

You can also read cookie values directly using event.get() thanks to the smart accessor API.

Likewise, event.query.get('page') or event.get('page') will fetch query parameters.

Routing Integration

The IncomingBrowserEvent supports route integration via internal route resolvers:

Important

This API is only available when the router is active. If you’re not using the router, these methods will return undefined.

event.getRoute() // Current matched route (if any)

event.params // An object with all route parameters

event.getParam('id') // Route param (e.g., `/user/:id`)

This allows you to access dynamic route parameters directly from the incoming event, making it easy to build SPAs with Stone.js.

User Environment Detection

You can safely introspect the browser’s environment using:

event.userAgent // Returns navigator.userAgent

event.isSecure // Returns true if protocol is https

Smart get() Strategy

IncomingBrowserEvent inherits the smart accessor from IncomingEvent, but overrides its lookup order to favor browser-specific sources:

- Route parameters (If using the router)

- Query parameters

- Cookies

- Metadata

This means that in browser applications, calling:

event.get('theme', 'light')

Will try to find theme from:

- A dynamic route segment (e.g.,

/theme/:theme) - A query string like

?theme=dark - A cookie like

theme=dark - A metadata store (if set by middleware)

- Fallback to

'light'if not found

No need to manually inspect cookies, query strings, or params, the browser event does it all for you. This makes your code cleaner and more maintainable, as you can rely on a consistent API for accessing data regardless of its source.

Feel free to use the specific accessors if you need to be explicit about the source.

Using IncomingHttpEvent

IncomingHttpEvent is the most advanced subclass of IncomingEvent. It is created automatically by HTTP-compatible adapters such as:

@stone-js/node-http-adapter(Node.js HTTP/HTTPS server)@stone-js/aws-lambda-http-adapter(Lambda HTTP functions)- Any custom HTTP adapter you implement

It is designed to encapsulate everything about an incoming HTTP request in a platform-agnostic and feature-rich way, without ever dealing directly with raw HTTP request objects.

It includes everything from IncomingEvent and IncomingBrowserEvent, and expands it to support HTTP-specific semantics like methods, headers, request bodies, uploaded files, content negotiation, and caching headers.

Constructor Reference

| Property | Type | Description |

|---|---|---|

url | URL | Required. The full request URL |

ip | string | Required. The client’s IP address |

ips | string[] | Optional. Proxy IP chain if available |

method | HttpMethod | Optional. The HTTP method (default: 'GET') |

headers | Headers or Record<string,string> | Optional. Parsed request headers |

body | Record<string, unknown> | Optional. Parsed request body |

files | Record<string, UploadedFile[]> | Optional. Uploaded files (if any) |

queryString | string | Optional. Raw query string |

cookies | CookieCollection | Optional. Parsed cookies |

source | IncomingEventSource | Required. Raw request data from the adapter |

locale | string | Optional. The preferred locale (default: 'en') |

metadata | Record<string, unknown> | Optional. Initial internal metadata |

You will never manually instantiate this event. It is built by the adapter and passed to your event handler automatically.

Don't forget!

You can participate in the creation process using adapter middleware.

URL, Method, and Routing Access

Just like IncomingBrowserEvent, you can retrieve and manipulate URL-related information.

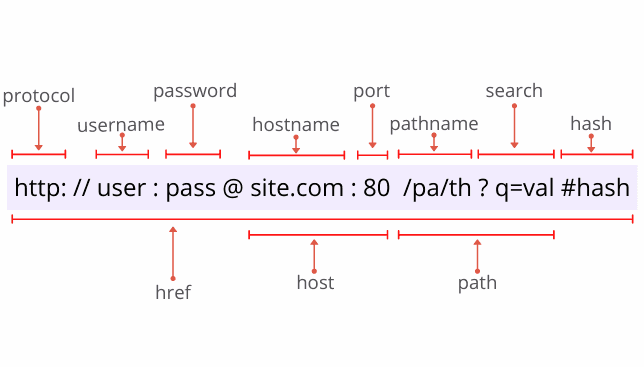

For example, consider this URL: http://user:pass@site.com:80/pa/th?q=val#hash, represented by this image:

Here’s how to access this URL and its components:

event.url // returns the full URL

event.uri // returns "http://user:pass@site.com:80/pa/th?q=val#hash"

event.protocol // returns "http"

event.host // returns "site.com:80"

event.hostname // returns "site.com"

event.path // returns "/pa/th?q=val"

event.pathname // returns "/pa/th"

event.segments // returns ['pa', 'th']

event.queryString // returns "?q=val"

event.query // returns URLSearchParams { 'q' => 'val' }

event.hash // returns "#hash"

You can also check the request method:

// Get HTTP method

event.method // returns 'GET'

// Inspect method

event.isMethod('GET') // returns `true` or `false`

event.isMethodSafe() // returns `true` for ['GET', 'HEAD', 'OPTIONS', 'TRACE']

event.isMethodCacheable() // returns `true` for ['GET', 'HEAD']

Route information is also accessible if you’re using the Stone.js Router:

event.params // returns an object with all route parameters

event.getRoute() // full route object

event.getParam('id', 'default') // from route

Headers and Content Negotiation

The IncomingHttpEvent exposes full control over headers via:

// Get headers

event.headers // returns Headers instance

// Get header

event.getHeader('authorization') // returns "Bearer XXXXXX"

// Default value

event.getHeader('x-custom-header', 'my-header') // returns "my-header"

// Has header

event.hasHeader('authorization') // returns `true` or `false`

It also handles content negotiation through:

event.types // Acceptable types

event.charsets // Acceptable charsets

event.languages // Acceptable languages

event.encodings // Acceptable encodings

// Get content-type

event.contentType // returns 'application/json'

// Get content-type charset

event.charset // returns 'utf-8'

// Returns the first accepted type.

// If nothing in types is accepted, then false is returned.

event.acceptsTypes('json', 'html')

// Returns the first accepted encoding.

// If nothing in encodings is accepted, then false is returned.

event.acceptsEncodings('gzip', 'deflate')

// Returns the first accepted charset.

// If nothing in charsets is accepted, then false is returned.

event.acceptsCharsets('utf-8')

// Returns the first accepted language.

// If nothing in languages is accepted, then false is returned.

event.acceptsLanguages('en-US')

Request Body and JSON

For HTTP requests that include a body, you can access and inspect it through:

event.body // the full parsed body

event.json('user.name', 'default') // deep access or default value

event.hasJson('user.isAdmin') // check existence

This enables safe and expressive handling of incoming data, especially for APIs receiving structured JSON payloads.

File Uploads

If your adapter supports multipart/form-data, uploaded files are accessible via:

event.files // returns all uploaded files Record<string, UploadedFile[]>

event.files.avatar // returns UploadedFile[]

event.getFile('document') // shorthand

event.hasFile('resume') // check existence

You can filter uploaded files:

// Get filtered uploaded files

const files = event.filterFiles(['documents', 'images'])

const documents = files.documents // returns UploadedFile[]

Each UploadedFile provides utilities:

file.isValid()

file.getSize()

file.getPath()

file.getClientMimeType()

file.guessClientExtension()

file.getClientOriginalName()

file.getClientOriginalExtension()

You can save a file using the move method, which takes the relative path of the directory where the file will be saved as a mandatory parameter and an optional parameter to specify the name used for saving the file:

// Get the first valid file

const document = event.getFile('documents').find(document => document.isValid())

// Save with client filename

document?.move('./files-directory/')

// Save with provided filename

document?.move('./files-directory/', 'file-doc-01')

This makes server-side file handling secure, consistent, and predictable.

Enabling Body and File Uploads

Stone.js is designed to be fast and lightweight by default. To keep bundle size and boot time minimal, body parsing and file upload handling are opt-in features, not included unless explicitly added.

To access:

event.bodyevent.filesevent.json()event.getFile()

You must register the corresponding middleware:

| Middleware Name | Purpose |

|---|---|

BodyEventMiddleware | Parses the incoming request body into event.body |

FilesEventMiddleware | Parses uploaded files into event.files and helpers |

These middleware are shipped in each HTTP adapter but are not installed by default. You must explicitly register them using the blueprint.

Each adapter provides its own compatible middleware, so you must only use middleware from the adapter you're working with.

Example: Registering with Node HTTP Adapter

Here is a declative and imperative example of how to register the body and file upload middleware with the Node HTTP adapter.

Declarative registration

To register the middleware declaratively, use the middleware option within the @NodeHttp() decorator. This approach allows you to specify the middleware directly in the adapter configuration, ensuring a clean and concise setup.

import {

NodeHttp, BodyEventMiddleware, FilesEventMiddleware

} from '@stone-js/node-http-adapter'

@NodeHttp({

middleware: [

BodyEventMiddleware,

FilesEventMiddleware

]

})

export class Application {}

Imperative registration

To register the middleware imperatively, you can use the defineAdapterMiddleware() function.

import {

BodyEventMiddleware, FilesEventMiddleware

} from '@stone-js/node-http-adapter'

import {

defineBlueprintConfig, defineAdapterMiddleware

} from '@stone-js/core'

export const mainBlueprint = defineBlueprintConfig({

afterConfigure(blueprint) {

blueprint.set(

defineAdapterMiddleware([BodyEventMiddleware, FilesEventMiddleware])

)

}

})

You must use the afterConfigure() hook to register these middlewares, because the adapter is resolved at runtime, not statically. That’s part of Stone.js’s continuum flexibility: you can switch adapters dynamically, but it also means you must wait until the adapter is known to bind adapter-specific middleware.

HTTP-Specific Features

You also get access to:

- Fingerprinting: generate a unique hash for this request

event.fingerprint() // uses method + path

event.fingerprint(true) // includes IP + user-agent

- Caching Support:

event.isFresh(response) // check cache freshness

event.isStale(response) // inverse

- Range Requests:

event.range(1024) // parses range header

- Content Type Detection:

event.is('json', 'html') // checks against content-type

event.getMimeType('svg') // from extension

event.getFormat('image/png') // from mime type

Cookie Access

The cookie API is consistent with IncomingBrowserEvent, and follows the continuum cookie contract. Stone.js guarantees that the same cookie access and mutation logic works identically across both client and server.

event.getCookie('auth_token', {}) // Return a Cookie object or default value

event.cookies.getValue('auth_token') // Get the cookie value directly

event.hasCookie('isLoggedIn')

Tips

Stone.js provides a dedicated Cookie documentation page, where you’ll find all available methods and usage examples.

The cookie API is unified across the continuum, frontend and backend behave the same.

Smart get() Lookup Strategy

This is where IncomingHttpEvent shines.

The get() method checks each of the following in order:

- Route parameters

- Body

- Query string

- Headers

- Cookies

- Metadata

- Fallback value

This makes it incredibly flexible and consistent. For example:

event.get('userId')

Works whether:

- You passed it as a URL param (

/user/:userId) - In the body of a POST request

- As a query param (

?userId=123) - In a custom header

- Even as a cookie

- Or in the metadata store

- And as a fallback value

Write your logic once. It works everywhere.

Other Utilities

Other useful getters to retrieve and inspect HTTP elements:

event.ip: The IP addressevent.ips: The IP addressesevent.isSecure: Checks if the request is secure (https)event.isXhr/event.isAjax: Checks if the request is anXMLHttpRequestevent.userAgent: The user agentevent.isPrefetch: Checks if it is a prefetch request

Configuring IncomingHttpEvent

Stone.js allows you to configure how HTTP events are built and filtered before they ever reach your application. These configurations belong to the integration dimension and act as system-level guards, validating inputs, limiting payloads, and ensuring safe defaults.

Misconfigured or malicious requests are rejected before they become part of the internal context, preventing invalid IncomingHttpEvent instances from reaching your code.

Trusted Proxies

When running behind a proxy (e.g., NGINX, Cloudflare, Vercel Edge), information like IP address, hostname, or protocol may be rewritten. To ensure Stone.js can restore the original data, you must specify which proxies you trust.

Use the following blueprint namespaces:

stone.http.proxies.trustedIp, IP ranges or CIDRs considered trustworthystone.http.proxies.untrustedIp, IPs to explicitly deny

Do not use both simultaneously.

@Configuration()

export class MyConfig implements IConfiguration {

configure(blueprint: IBlueprint) {

blueprint

.set('stone.http.proxies.trustedIp', ['127.0.0.0/8', '10.0.0.0/8'])

.set('stone.http.proxies.untrustedIp', ['192.168.0.0/16'])

}

}

Use '*' to allow all proxies (or block all, depending on your needs):

blueprint.set('stone.http.proxies.trustedIp', ['*'])

Body Configuration

To limit memory usage and attack vectors, Stone.js lets you define strict limits on request bodies:

blueprint.set('stone.http.body', {

limit: '1mb',

defaultType: 'application/json',

defaultCharset: 'utf-8'

})

This config ensures the adapter knows how much data to read, how to decode it, and what to assume when no content-type is set.

File Upload Configuration

Stone.js uses busboy internally to parse multipart/form-data uploads. You can customize busboy options directly via:

blueprint.set('stone.http.files.upload', {

limits: {

fileSize: 2 * 1024 * 1024 // 2MB per file

},

highWaterMark: 128 * 1024

})

See the busboy documentation for a full list of available options.

This allows you to control:

- Maximum file sizes

- Number of files

- Buffer size

- Accepted MIME types (via file extension config, see below)

Other Notable Options

| Namespace | Purpose |

|---|---|

stone.http.hosts.trusted | List of valid hostnames |

stone.http.hosts.trustedPattern | Regex-like patterns for valid hosts |

stone.http.subdomain.offset | Position to parse subdomains from hostname |

In short, HTTP configuration lets you control what enters your system, which payloads, from whom, in what form, and how much of it.

It’s your first line of defense, and a perfect place to enforce consistency and safety across all environments.

When to use it?

Stone.js comes with carefully chosen defaults that suit most applications, while still allowing you to customize settings when specific needs arise.

Best Practices

The IncomingEvent and its platform-specific subclasses are at the heart of every Stone.js application. They represent the user’s intention, and everything else in your app is just a reaction.

Here’s how to use them wisely.

Never Access IncomingEvent in Constructor-Injection

The IncomingEvent does not exist during system boot. It is only created during runtime, after the adapter has received an external cause and onHandlingEvent hooks have been triggered.

Trying to access the event in a constructor-injected service will cause hard-to-debug issues:

@Stone()

export class BadService {

constructor({ event }: { event: IncomingEvent }) {

// ❌ This will break, IncomingEvent isn't available yet

}

}

Instead: access the event in methods called at runtime, like inside your handler, middleware, or lifecycle hooks.

Prefer get() Over Manual Inspection

Avoid branching logic like this:

if (event instanceof IncomingHttpEvent) {

return event.body.user?.name

} else {

return event.get('user.name')

}

Just use the smart get():

const name = event.get('user.name')

It handles the lookup strategy internally and gives you consistent results, even across environments like Lambda, Node, CLI, and browser.

Don’t Overuse event.source

While source.rawEvent and source.platform are useful for introspection and debugging, avoid hard-coding platform-specific behavior in your logic:

if (event.source.platform === 'aws_lambda') {

// ❌ This defeats the platform-agnostic design

}

If you need data from rawEvent, extract it with a middleware and inject it into metadata instead. That way your handlers remain clean and reusable.

Use Middleware to Enrich, Not Mutate

If you want to add useful information to the event (like a user object, request ID, permissions), do it via set() in a middleware:

event.set('user.id', '123')

Don’t attempt to change properties like url, method, or body, treat the core of the event as immutable.

Install Only the Middleware You Need

By default, Stone.js does not include body parsers or file handlers to keep your app lean. Only register BodyEventMiddleware and FilesEventMiddleware when needed:

blueprint.set(

defineAdapterMiddleware([BodyEventMiddleware])

)

This is especially useful for API-first microservices or endpoints that don’t receive body content.

Use Event Subclasses for Rich Capabilities

Don't stick to IncomingEvent just because it’s generic. If your context is HTTP, use IncomingHttpEvent, it gives you content negotiation, headers, method checks, body helpers, and more.

If you’re in a browser, IncomingBrowserEvent gives you SPA navigation support, cookie helpers, and segment parsing.

Stone.js will inject the correct subclass for you, just type your handler’s parameter accordingly:

handle(event: IncomingHttpEvent) {

// Full HTTP capabilities available here

}

Summary

The IncomingEvent system in Stone.js is the central interface through which your application receives and interprets intentions from the outside world, whether from HTTP requests, browser navigations, CLI commands, or serverless platforms.

Here’s what you should remember:

Everything Starts with the Intention

- An IncomingEvent is not a controller or handler, it’s the normalized intention sent to your domain.

- It’s created by the adapter at runtime, not by you, and only after the platform has triggered the app’s lifecycle.

- You never mutate it, you interact with it through safe APIs (

get,set,clone). - You can participate in its creation using adapter middleware.

Three Forms, One Continuum

IncomingEvent: Generic, metadata-based, used for CLI, Lambda, lightweight adapters.IncomingBrowserEvent: Used for SPA and SSR navigation in the browser. Triggered by navigation events only.IncomingHttpEvent: The richest event type. Supports methods, headers, bodies, cookies, file uploads, and more.

Each one builds upon the last, features accumulate from base to top. No duplicated logic. No surprises.

One Unified API

- All incoming events use the same core API:

get(),set(),clone()- Dot notation support

- Platform-aware data resolution

- Write your handler logic once, it works on Node, Lambda, CLI, and local dev without changes.

Platform Features Are Opt-In

- Want to handle request bodies? Add

BodyEventMiddleware. - Need to parse uploaded files? Add

FilesEventMiddleware. - Want to limit request size, restrict IPs, or enforce content types? Use the configuration blueprint.

- Nothing is included by default, you opt-in to what your app needs.

Think Dimensionally

- The adapter belongs to the integration dimension, it translates external chaos into internal order.

- The

IncomingEventlives in the initialization dimension, it’s now ready for business logic, services, and response generation. - Middleware is the bridge, the place to enrich or sanitize the event before it reaches your handlers.

With IncomingEvent, you don’t just handle requests.

You handle intentions, consistently, across space (platforms) and time (contexts).

Welcome to the Continuum 😎